Prerequisites

These articles are meant to help you learn how to use three.js.

They assume you know how to program in JavaScript. They assume

you know what the DOM is, how to write HTML as well as create DOM elements

in JavaScript. They assume you know how to use

es6 modules

via import and via <script type="module"> tags. They assume you know how to use import maps.

They assume you know some CSS and that you know what

CSS selectors are.

They also assume you know ES5, ES6 and maybe some ES7.

They assume you know that the browser runs JavaScript only via events and callbacks.

They assume you know what a closure is.

Here's some brief refreshers and notes

es6 modules

es6 modules can be loaded via the import keyword in a script

or inline via a <script type="module"> tag. Here's an example

<script type="importmap">

{

"imports": {

"three": "./path/to/three.module.js",

"three/addons/": "./different/path/to/examples/jsm/"

}

}

</script>

<script type="module">

import * as THREE from 'three';

import {OrbitControls} from 'three/addons/controls/OrbitControls.js';

...

</script>

See more details at the bottom of this article.

document.querySelector and document.querySelectorAll

You can use document.querySelector to select the first element

that matches a CSS selector. document.querySelectorAll returns

all elements that match a CSS selector.

You don't need onload

Lots of 20yr old pages use HTML like

<body onload="somefunction()">

That style is deprecated. Put your scripts at the bottom of the page.

<html>

<head>

...

</head>

<body>

...

</body>

<script>

// inline javascript

</script>

</html>

Know how closures work

function a(v) {

const foo = v;

return function() {

return foo;

};

}

const f = a(123);

const g = a(456);

console.log(f()); // prints 123

console.log(g()); // prints 456

In the code above the function a creates a new function every time it's called. That

function closes over the variable foo. Here's more info.

Understand how this works

this is not magic. It's effectively a variable that is automatically passed to functions just like

an argument is passed to function. The simple explanation is when you call a function directly

like

somefunction(a, b, c);

this will be null (when in strict mode or in a module) where as when you call a function via the dot operator . like this

someobject.somefunction(a, b, c);

this will be set to someobject.

The parts where people get confused is with callbacks.

const callback = someobject.somefunction; loader.load(callback);

doesn't work as someone inexperienced might expect because when

loader.load calls the callback it's not calling it with the dot . operator

so by default this will be null (unless the loader explicitly sets it to something).

If you want this to be someobject when the callback happens you need to

tell JavaScript that by binding it to the function.

const callback = someobject.somefunction.bind(someobject); loader.load(callback);

this article might help explain this.

ES5/ES6/ES7 stuff

var is deprecated. Use const and/or let

There is no reason to use var EVER and at this point it's considered bad practice

to use it at all. Use const if the variable will never be reassigned which is most of

the time. Use let in those cases where the value changes. This will help avoid tons of bugs.

Use for(elem of collection) never for(elem in collection)

for of is new, for in is old. for in had issues that are solved by for of

As one example you can iterate over all the key/value pairs of an object with

for (const [key, value] of Object.entries(someObject)) {

console.log(key, value);

}

Use forEach, map, and filter where useful

Arrays added the functions forEach,

map, and

filter and

are used fairly extensively in modern JavaScript.

Use destructuring

Assume an object const dims = {width: 300, height: 150}

old code

const width = dims.width; const height = dims.height;

new code

const {width, height} = dims;

Destructuring works with arrays too. Assume an array const position = [5, 6, 7, 1];

old code

const y = position[1]; const z = position[2];

new code

const [, y, z] = position;

Destructuring also works in function arguments

const dims = {width: 300, height: 150};

const vector = [3, 4];

function lengthOfVector([x, y]) {

return Math.sqrt(x * x + y * y);

}

const dist = lengthOfVector(vector); // dist = 5

function area({width, height}) {

return width * height;

}

const a = area(dims); // a = 45000

Use object declaration short cuts

old code

const width = 300;

const height = 150;

const obj = {

width: width,

height: height,

area: function() {

return this.width * this.height

},

};

new code

const width = 300;

const height = 150;

const obj = {

width,

height,

area() {

return this.width * this.height;

},

};

Use the rest parameter and the spread operator ...

The rest parameter can be used to consume any number of parameters. Example

function log(className, ...args) {

const elem = document.createElement('div');

elem.className = className;

elem.textContent = args.join(' ');

document.body.appendChild(elem);

}

The spread operator can be used to expand an iterable into arguments

const position = [1, 2, 3]; someMesh.position.set(...position);

or copy an array

const copiedPositionArray = [...position]; copiedPositionArray.push(4); // [1,2,3,4] console.log(position); // [1,2,3] position is unaffected

or to merge objects

const a = {abc: 123};

const b = {def: 456};

const c = {...a, ...b}; // c is now {abc: 123, def: 456}

Use class

The syntax for making class like objects pre ES5 was unfamiliar to most

programmers. As of ES5 you can now use the class

keyword

which is closer to the style of C++/C#/Java.

Understand getters and setters

Getters and

setters are

common in most modern languages. The class syntax

of ES5 makes them much easier than pre ES5.

Use arrow functions where appropriate

This is especially useful with callbacks and promises.

loader.load((texture) => {

// use texture

});

Arrow functions bind this to the context in which you create the arrow function.

const foo = (args) => {/* code */};

is a shortcut for

const foo = (function(args) {/* code */}).bind(this));

See link above for more info on this.

Promises as well as async/await

Promises help with asynchronous code. Async/await help use promises.

It's too big a topic to go into here but you can read up on promises here and async/await here.

Use Template Literals

Template literals are strings using backticks instead of quotes.

const foo = `this is a template literal`;

Template literals have basically 2 features. One is they can be multi-line

const foo = `this is a template literal`; const bar = "this\nis\na\ntemplate\nliteral";

foo and bar above are the same.

The other is that you can pop out of string mode and insert snippets of

JavaScript using ${javascript-expression}. This is the template part. Example:

const r = 192;

const g = 255;

const b = 64;

const rgbCSSColor = `rgb(${r},${g},${b})`;

or

const color = [192, 255, 64];

const rgbCSSColor = `rgb(${color.join(',')})`;

or

const aWidth = 10;

const bWidth = 20;

someElement.style.width = `${aWidth + bWidth}px`;

Learn JavaScript coding conventions.

While you're welcome to format your code any way you chose there is at least one convention you should be aware of. Variables, function names, method names, in JavaScript are all lowerCasedCamelCase. Constructors, the names of classes are CapitalizedCamelCase. If you follow this rule your code will match most other JavaScript. Many linters, programs that check for obvious errors in your code, will point out errors if you use the wrong case since by following the convention above they can know when you're using something incorrectly.

const v = new vector(); // clearly an error if all classes start with a capital letter const v = Vector(); // clearly an error if all functions start with a lowercase letter.

Consider using Visual Studio Code

Of course use whatever editor you want but if you haven't tried it consider using Visual Studio Code for JavaScript and after installing it setup eslint. It might take a few minutes to setup but it will help you immensely with finding bugs in your JavaScript.

Some examples

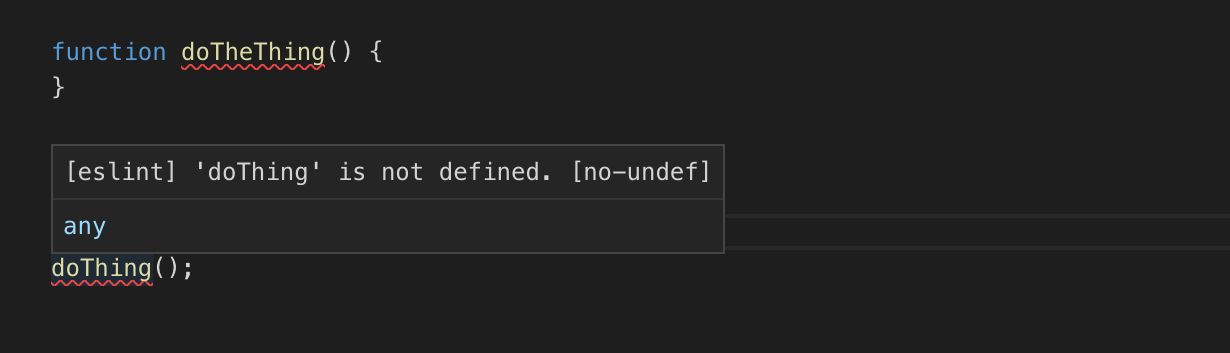

If you enable the no-undef rule then

VSCode via ESLint will warn you of many undefined variables.

Above you can see I mis-spelled doTheThing as doThing. There's a red squiggle

under doThing and hovering over it it tells me it's undefined. One error

avoided.

If you're using <script> tags to include three.js you'll get warnings using THREE so add /* global THREE */ at the top of your

JavaScript files to tell eslint that THREE exists. (or better, use import 😉)

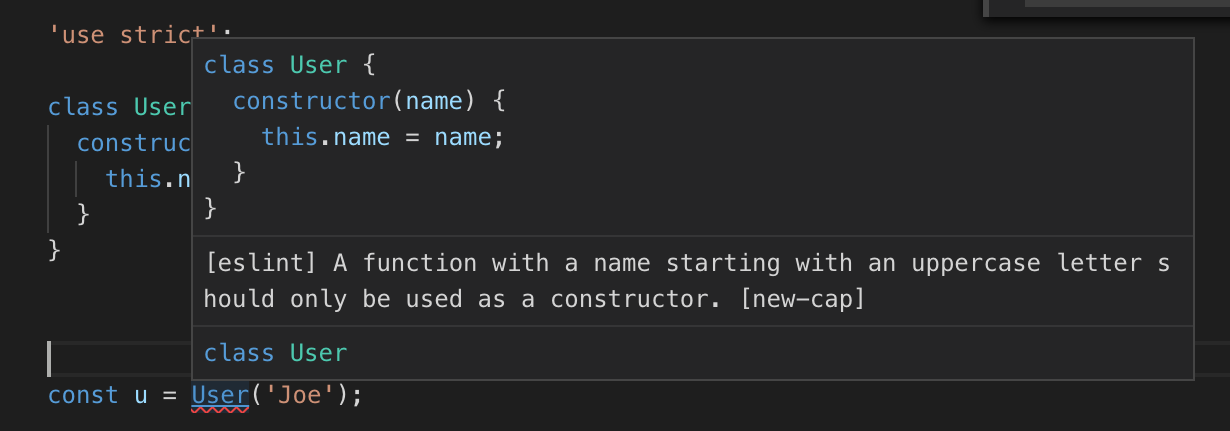

Above you can see eslint knows the rule that UpperCaseNames are constructors

and so you should be using new. Another error caught and avoided. This is the

new-cap rule.

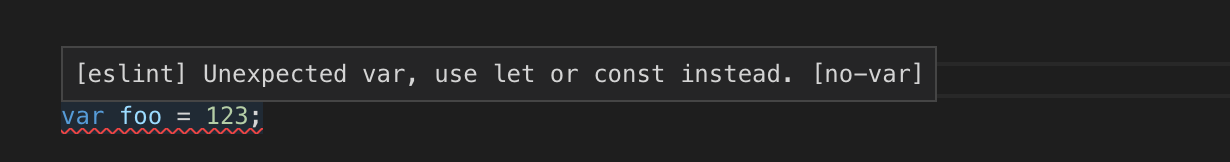

There are 100s of rules you can turn on or off or

customize. For example above I mentioned you

should use const and let over var.

Here I used var and it warned me I should use let or const

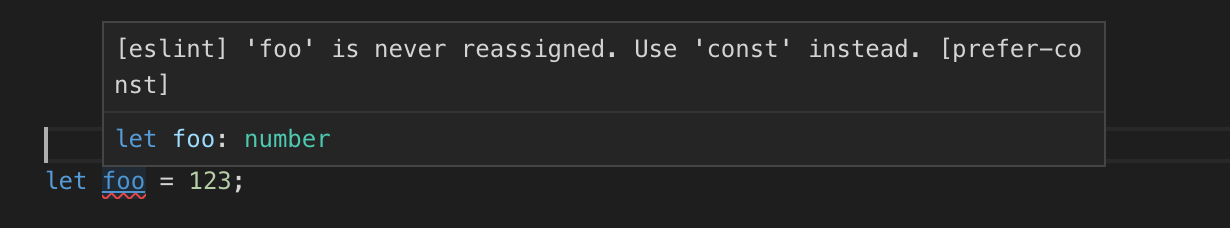

Here I used let but it saw I never change the value so it suggested I use const.

Of course if you'd prefer to keep using var you can just turn off that rule.

As I said above though I prefer to use const and let over var as they just

work better and prevent bugs.

For those cases where you really need to override a rule you can add comments to disable them for a single line or a section of code.

If you really need to support legacy browsers use a transpiler

Most modern browsers are auto-updated so using all these features will help you be productive and avoid bugs. That said, if you're on a project that absolutely must support old browsers there are tools that will take your ES5/ES6/ES7 code and transpile the code back to pre ES5 Javascript.